Flash from the past: Why an apparent Israeli nuclear test in 1979 matters today

/Published September 8th, 2015 By Leonard Weiss in Bulletin of Atomic Scientists

At a time when the Iran agreement is in the headlines and other Middle Eastern countries—notably Saudi Arabia—are making noises about establishing their own programs for nuclear energy and nuclear weapons, it is worth giving renewed scrutiny to an event that occurred 36 years ago: a likely Israeli-South African nuclear test over the ocean between the southern part of Africa and the Antarctic. Sometimes referred to in the popular press as the “Vela Incident” or the “Vela Event of 1979," the circumstantial and scientific evidence for a nuclear test is compelling but as long as many items related to the test are still classified, all the questions surrounding it cannot be resolved definitively. Those questions allow wiggle room for some observers (a shrinking number) to still doubt whether the event was of nuclear origin. But more and more information revealed in various publications over the years strongly supports the premise that a mysterious double flash detected by a US satellite in 1979 was indeed a nuclear test performed by Israel with South African cooperation, in violation of the Limited Test Ban Treaty. The US government, however, found it expedient to brush important evidence under the carpet and pretend the test did not occur.

The technical evidence—evidence that has been reviewed in earlier publications—led scientists at US national laboratories to conclude that a test took place. But to this should be added more recent information of Israeli-South African nuclear cooperation in the 1970s, and at least two instances—so far unverified—of individuals claiming direct knowledge of, or participation in, the nuclear event, one from the Israeli side and one from the South African. And information provided by national laboratory scientists regarding the state of the satellite’s detectors challenges the view given by a government panel that the flash was likely not that of a nuclear test.

The US government’s use of classification and other means to suppress public information about the event, in the face of the totality of technical and non-technical evidence supporting a nuclear test, could be characterized as a cover-up to avoid the difficult international political problems that a recognized nuclear test was assumed to trigger.

This cover-up is all the more troubling because it runs contrary to President Obama’s speech in Prague in 2009, in which he stated: “To achieve a global ban on nuclear testing, my administration will immediately and aggressively pursue US ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. After more than five decades of talks, it is time for the testing of nuclear weapons to finally be banned.” Later, in the same speech, he said: “We go forward with no illusions. Some will break the rules, but that is we need a structure in place that ensures that when any nation does, they will face consequences.”

Yet Israel and South Africa broke the rules, but they did not face consequences. All of this is more than “ancient history;” there is no statute of limitations on nuclear arms agreement violations.

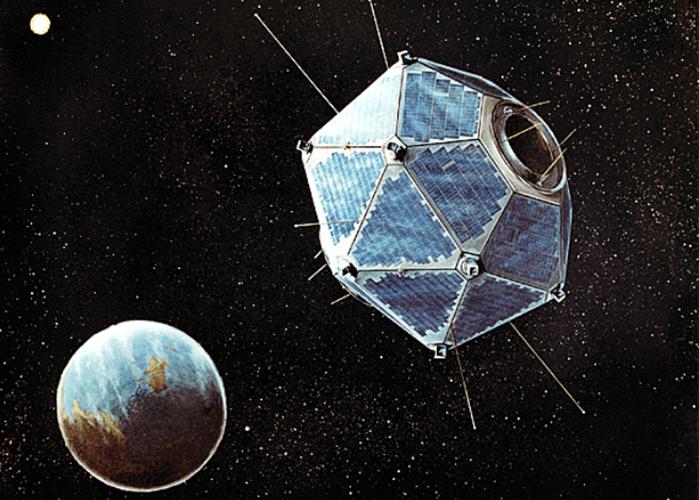

What happened. On September 22, 1979, a US satellite code-named Vela 6911, which was designed to look for clandestine atmospheric nuclear tests and had been in operation for more than 10 years, recorded a double flash in an area where the South Atlantic meets the Indian Ocean, off the coast of South Africa. The detection immediately triggered a series of steps in which analysts at national labs in the United States informed their superiors that the recorded signal had all the earmarks of a nuclear test. (Some details about exactly what the analysts did has been written about in Jeffrey Richelson’s 2007 book, Spying on the Bomb.) The event has been a subject of controversy ever since, but is now recognized by most analysts as the detection of an Israeli nuclear test with South African logistical cooperation.

The Air Force Technical Analysis Center gave the event the formal designation of Alert (A) 747. Shortly afterward, President Jimmy Carter and his national security team were informed. In his diary entry of September 22, later published in 2010 as White House Diary, the former president wrote, “There was indication of a nuclear explosion in the region of South Africa—either South Africa, Israel using a ship at sea, or nothing.”

Already, a process of elimination based on intelligence information had quickly narrowed the possible perpetrators to two: South Africa and Israel. An effort was immediately launched to seek corroborative evidence. No radioactive fallout was detected, but hydro-acoustic and wave data collected by ocean sensors and later analyzed by the Naval Research Laboratory showed that an unusual and unmistakable event had taken place. In addition, a new, highly sensitive radio-telescope at the Arecibo Laboratory—home of the world’s largest single radio-telescope—reported the detection of an anomalous ionospheric travelling wave at about the same time as the Vela recordings. “Almost certainly, there was a large influx of energy somewhere over South Africa at about the time the Vela satellite saw its flash,” concluded Arecibo physicist Richard Behnke.

The initial opinions of the scientists at the national labs that a test had occurred and that Israel was a prime suspect unnerved the White House and the State Department. (“Sheer panic,” then-Assistant Secretary of State Hodding Carter was reported as saying in investigative reporter Seymour Hersh’s 1991 book, The Samson Option). Announcing the detection of a nuclear test without knowing and naming the perpetrator would be a serious political and national security problem for the White House. It would mean that the system for detecting violations of the 1962 Limited Test Ban Treaty by the Soviets or others was seriously flawed, which could jeopardize the ratification of the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty II, then lying before the Senate. It could also undermine the administration’s claims of success in its nonproliferation policies if it was unable to identify a clandestine test by a proliferating state.

Moreover, if Israel was involved, the administration feared serious negative effects on the prospects for peace in the Middle East, including the possible unraveling of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and the accompanying diminishment of Carter’s efforts in brokering a peace settlement between Israel and Egypt. In addition, the administration had recently punished Pakistan with an aid cutoff for pursuing a clandestine nuclear program in violation of US law. Thus, if Israel was the known nuclear perpetrator, ignoring an Israeli nuclear test would make for a glaring case of a double standard in US non-proliferation policy.

Imposing sanctions on Israel, on the other hand, would be a political disaster, involving a major loss of support for the administration among the Jewish diaspora in the United States, an important political constituency for Carter and the Democratic Party. For all these reasons, the administration was highly motivated to offer some explanation other than a nuclear test for the Vela event and to hide, suppress, or otherwise soft-pedal information and evidence to the contrary—in other words, to engage in a cover-up. In this case, a cover-up would not involve criminality, as in the Watergate affair of the Nixon Administration, but rather offer a way of avoiding a difficult political decision with potentially serious international ramifications for US policy on arms control, non-proliferation, and the Middle East generally. This cover-up would also protect existing policy regarding Israel’s nuclear weapons program, which federal officials are routinely admonished not to discuss publicly.

The Ruina panel. Finding a credible alternative, if possible, to the prevailing scientific consensus already formed within the national labs that a test had occurred required time and a broadening of the range of scientific opinion. Both requirements were met by the expedient of creating an eight-member, blue-ribbon scientific panel to review the data and the reports collected up to that point. Spurgeon Keeny—then the deputy director of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency—told me in an interview on July 30, 2004 that the idea for the outside panel was his. (Although the panel was to officially take its mandate from and report to Frank Press, the president’s science adviser and head of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.)

The panel contained a Nobel Prize-winner, Luis Alvarez, and seven other notable scientists, including Richard Garwin—who had been deeply involved in national security scientific affairs and would become one of the most active panel members. The designated chair was Jack Ruina, a well-connected professor of electrical engineering at MIT and a friend of Press. Ruina became the public face of the panel, although the panel would never hold a public hearing of any kind. The Ruina panel began work on November 1, 1979, five days after Carter wrote in his diary: “At the foreign affairs breakfast we went over the South Africa nuclear explosion, we still don’t know who did it.” Carter kept receiving briefings on the Vela event as the Ruina panel performed its task, and, referring to the prevailing opinion at the national labs, on February 27, 1980 he wrote in his diary: “We have a growing belief among our scientists that the Israelis did indeed conduct a nuclear test explosion in the ocean near the southern end of South Africa.” Nonetheless, the Ruina panel issued a classified report in the spring of 1980, concluding that the Vela event was likely not a nuclear event, although they could not rule out a nuclear explosion. (An unclassified version was released in May that same year.)

The Ruina panel conclusion generates skepticism and disagreement at the national labs. In a 2011 paper for the Middle East Policy Council, I laid out the case for concluding that the Vela event was an Israeli nuclear test assisted logistically by the South African navy. The evidence included technical reports or statements concluding that (A) 747 was likely a nuclear test, issued by scientists at the Los Alamos and Sandia national laboratories, the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), and the Nuclear Intelligence Panel headed by Donald Kerr, who was famously quoted as saying, “We had no doubt it was a bomb.”

According to the former director of NRL, Alan Berman, his lab produced a 300-page report which he said was unequivocal in concluding that (A) 747 was a nuclear test. This report has never been declassified, and the White House subsequently ignored it—over the protests of Berman. In addition, the Carter Administration made sure that the Ruina panel report—containing the result that the White House was looking for, that the Vela incident was probably not a nuclear event—was released a month ahead of the delivery to the White House of the Naval Research Laboratory report. By thus cherry-picking reports and manipulating the classification procedure, the strategists on the issue at the White House could get the results they wanted, and then publicize them.

As a result of information I received in my capacity as the staff director of a Senate subcommittee on nuclear nonproliferation issues, I had concluded that the Vela event was a nuclear test and said so in private meetings. I had been warned by a Carter administration official that my reputation would suffer if I were to express my opinion publicly. Nonetheless I was willing to do so, and I agreed to give an on-camera interview at the request of CBS News on March 6, 1981. Somehow, the White House (now in the hands of the Reagan administration) learned of the scheduled interview and intervened with my then-boss, Sen. John Glenn, to prevent me from uttering my opinion that a test had occurred. This evidence of bi-partisan political panic on the issue made me realize that not only was (A) 747 a nuclear test, but that Israel was the likely perpetrator with South African support. Not being able to say what I really thought in the interview, but being required to go through with it, I simply expressed skepticism that the Ruina panel report should be considered the last word on the Vela event.

The Ruina panel’s narrow mandate and the bhangmeter phase anomaly issue. To this day, the Ruina panel report has been controversial and the subject of much comment and speculation.

Part of the problem: Although the panel was asked to determine whether a nuclear test had occurred, it was charged with examining only the scientific evidence and was not allowed to enter into the intelligence realm. That is, some of the most pertinent intelligence information—information that could have shed light on the motivation and capability for an Israeli test with South African assistance—was not within the panel’s realm to examine and analyze. (A subset of members did receive an intelligence briefing of some kind.)

There was plenty of such information to be examined. For example, in his 2010 book, The Unspoken Alliance, Sasha Polakow-Suransky revealed that in a meeting on March 31, 1975, Israel offered to sell nuclear-capable missiles to South Africa. In that same book, Polakow-Suransky wrote that in another meeting, on June 4, 1975, Israel's Shimon Peres told South African Defense Minister P.W. Botha that the “correct” (meaning nuclear) payloads for those missiles were available in three sizes. That transfer never occurred because South Africa was still in its early stage of nuclear development. Whether the US government knew of this at the time of the Ruina panel deliberations is currently unknown.

In any case, the panel stuck to its narrower mandate, reviewing only the available technical information regarding the recorded double flash to see if the data enabled concluding that the double flash was or was not a nuclear test, and also whether there was an alternative explanation. The panel disagreed with the opinion of the scientific director of the Naval Research Laboratory and dismissed the 300-page report by the laboratory as being insufficiently complete to conclude that a test took place.

As part of its search, the Ruina panel had a detailed examination performed on the signals recorded by the satellite’s two light detectors, called “bhangmeters.” Since the bhangmeters were designed to be identical except for sensitivity, the two signals would have been expected to be in synch chronologically (i.e., in phase) and consistent in terms of amplitude comparison. But it turned out that, although the two bhangmeter signals showed the classic shape of a nuclear double flash when graphed, there were anomalous phase differences that translated into inconsistent amplitudes between the two signals at certain times.

Two possible explanations were given by scientists who examined the data and were convinced that a test had taken place. One possibility was that the motion of the satellite itself would have enhanced the recorded strength of one of the bhangmeter signals. Another was a malfunction of one of the bhangmeters.

If neither explanation held, then it would be hard to explain the phase anomaly if the signal was that of a nuclear explosion—which is what the Ruina panel report seized on as a reason for skepticism that a nuclear test had occurred. The rejection by the panel of alternative explanations for the phase anomaly was bolstered by the claim that the anomaly was unique in the 10-year history of the satellite and that, in calibration tests of the bhangmeters, no malfunction was detected. The clear implication of the latter was that there was never any history of a malfunction of the bhangmeters when detecting a nuclear signal. This, however, is disputed by scientists at Los Alamos.

Did a malfunction cause the phase anomaly? According to researchers at Los Alamos, one of the bhangmeters began showing a malfunction as a result of aging. Referred to as a “timing tick,” it showed up whenever a nuclear flash was detected and recorded. In an email to me on July 27, 2012, Houston T. Hawkins, a senior fellow and the chief scientist in the Principal Associate Directorate for Global Security at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, wrote: “The two bhangmeters were purposeful [sic] designed to cover the entire range of yield possibilities. The ‘more sensitive’ one would detect very low level events but could be saturated at multi-megaton shots. The other ‘less sensitive’ bhangmeter would cover the higher levels but might not see very low (<1kt) level explosions. The magnitudes of the two bhangmeter signals in the 1979 event show these designed and expected differences.

"The Ruina Panel focused on a ‘timing tick’ that was seen in the 1979 event. However, this minor timing difference was a result of the aging of the sensors and electronics and had been seen on all of the more recent nuclear explosions that had occurred in Vela 6911’s field of view. Indeed, an absence of this Vela 6911 ‘timing tick’ in the case of the 1979 event would have been difficult to explain. Ironically, the ‘tic’ to our analysts was like a hallmark of authenticity.” (Emphasis in original.)

Thus the phase anomaly, according to Los Alamos, appeared to be the result of a malfunction that would not alter the signal’s double flash character. And although the Ruina panel claimed that the phase anomaly was a unique event, this has been challenged by at least one individual involved in the Vela incident. In any case, the tight correlation between the appearance of a “timing tick” and the detection of a real nuclear event is compelling.

The evident disagreement between the Ruina panel and Los Alamos on the state of the bhangmeters and on the cause of the phase anomaly is interesting but does not invalidate the claim by the lab that the (A) 747 signal from Vela 6911 was in keeping with all the previous signals generated by nuclear explosions detected by the satellite. It should be noted that the Vela satellites had detected all the known nuclear explosions that had occurred during their operation.

The Ruina panel went on to satisfy its mandate to provide an alternative non-nuclear explanation for the double flash. Its report offered a highly improbable scenario by which a double flash could have been produced through sunlight glinting off debris from a collision of the Vela satellite with a micrometeoroid.

On the other hand: No evidence that overt external political pressure affected the Ruina panel’s conclusions. As far as I know, no one in the scientific community within the labs had his opinion changed by the Ruina panel’s report or its subsequent defense by some panel members. Indeed, skepticism of the Ruina panel conclusion began as soon as the report was released, with questions raised as to whether the conclusion was the result of pressure generated by the intense desire of the Carter White House to deflect a finding of a nuclear test.

This should not have been a surprise to the panel members. They must have understood that by accepting and completing the task of finding an alternative explanation for the double flash regardless of its extremely low probability—and in the face of the existing consensus among the scientists within the US national nuclear security apparatus that a test had taken place—would result in the raising of questions about political influence or interference.

Certainly, the panelists would have been aware of the political consequences that would likely have ensued from a conclusion by them that a nuclear test had taken place. These were sophisticated men with great experience in national security policy matters, and needed no reminder of what was at stake.

But it strains credulity to believe that such well-known scientists would risk jeopardizing their credibility and reputations by committing an unnecessary political act that history would not judge kindly. Moreover, panel member Richard Garwin has continued over the years to defend the report and its conclusion, based mainly on the bhangmeter phase anomaly argument.

Consequently, internal or external pressure notwithstanding, there is no evidence that the panel members did anything other than give their genuine scientific opinion. The narrowness of their mandate, however, meant that their conclusion could not be definitive as to whether a test took place. Indeed, the panel recognized that deficiency by explicitly basing their conclusion in terms of probabilities and leaving open the possibility that a test did take place. A former colleague of Ruina at MIT, Marvin Miller, told me that Ruina worried about the perception of political influence when the panel’s report came out and was received with skepticism among scientists at the labs who had worked on the Vela event. It didn’t help when—in one of the few public statements he made about the panel’s report—he undermined the authority of its finding by stating that “two people looking at the same data could come to opposite conclusions.”

None of the scientists at Los Alamos backed up this statement.

The curious case of Ruina’s Israeli post-graduate student. After the Ruina panel closed up shop, Ruina continued to play a role in the history of the Vela event, which was illustrated via a story he told in writing to Spurgeon Keeny; the story has since become public. Keeny, who died in 2012, gave at least three interviews over several years beginning in 1989—to Seymour Hersh, Jeffrey Richelson, and myself—in which he related the story of an Israeli post-graduate student at MIT who had been deeply involved with Israel’s nuclear missile systems. The student indicated strongly to Ruina that the Vela event was an Israeli operation that the student had personal knowledge of. Keeny told Seymour Hersh that he and his colleagues in the Carter White House dismissed the student’s story as Israeli disinformation, and Hersh wrote that the information was not made known to the intelligence community or to other members of the Ruina panel. In his interview with me, however, Keeny said that Ruina passed this information to then-CIA Director Stansfield Turner. He did not know what Turner did with the information and did not know if Press or any other members of the Ruina panel had been informed. If there is a record of this, it is not publicly available.

It is important to note that while the Ruina panel’s conclusion was probably not the result of a political calculation by the panel, there is no denying that from the viewpoint of the Carter Administration, the panel had done just what was needed politically in coming up with an alternative explanation for the double flash. It inserted a note of uncertainty into the claim that (A) 747 was a nuclear event, enabling the administration to sidestep the issue.

It strains belief to think that this aim was unforeseen, when the idea for the Ruina panel was firstfloated. There is also no denying that the Carter White House and its immediate successor were anything but benign, impartial observers. The White House refused to declassify the NRL report and did not allow the Ruina panel to explore or consider extensive intelligence information regarding Israeli-South African nuclear and missile cooperation. It apparently suppressed the results of any investigation of Ruina’s Israeli post-graduate student. And in my own case, a Carter administration holdover working for the Reagan Administration apparently got my boss to order me to suppress my conclusion that the Vela event was a nuclear test.

Did the Israeli arsenal require a test? The Israelis are known to have developed boosted, miniaturized nuclear weapons; Israeli nuclear technician Mordecai Vanunu provided evidence of this to the British press in 1986. The Israelis are undoubtedly working on the design and development of thermonuclear weapons—if they have not already constructed one. None of the known weapons states has developed such advanced weapons without nuclear testing. That would have provided the motivation for Israel to carry out one or more nuclear tests (three, according to Hersh’s book), unless Israel received advanced nuclear weapon design codes and test data from a nuclear weapons state in violation of the NPT. (French assistance to Israel’s early nuclear weapon program in the 1950s came prior to the advent of the NPT and ended during the presidency of Charles de Gaulle).

There is no public evidence that Israel has been given or has stolen computer codes for advanced weapon design or associated test data that would make Israeli testing unnecessary. The Vela event could have been a test of the fission trigger for a thermonuclear weapon of Israeli design. Seymour Hersh was told by “former Israeli government officials” that it was a test of a low-yield, nuclear artillery shell, he wrote in The Samson Option. Thus, given what we now know about Israel’s nuclear capabilities, it is no surprise that believers in the Ruina panel’s alternative explanation of the Vela event constitute an increasingly small minority within the national security scientific community.

South Africa’s role: The saga of Lindsey Rooke. The last refuge of those who deny that a test took place is the failure so far to find and name an eyewitness or whistleblower.

The shield around this refuge, however, is developing cracks that suggest it is only a matter of time before a credible personal account surfaces. Besides Ruina’s post-graduate student, there is the curious case of a so-called “Lindsey Rooke,” a deceased female South African naval officer who ostensibly witnessed the test from a participating ship and described it in a diary she kept of the voyage to the test site. Portions of that diary were transcribed by a South African writer, Stacy Hardy, who is reluctant to reveal its whereabouts or the real name of Lindsey Rooke, because of fears of running afoul of South Africa’s stringent national security laws. (Hardy’s transcription is notable because it inspired Victor Gama, a well-known composer and musical instrument maker, to compose a multimedia work entitled “Vela 6911,” commissioned by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and performed at Stanford University. The work involves film, music, and a narration that describes the nuclear test, based on Hardy’s transcription.)

Attempts to elicit more information from Hardy about the Rooke diary have thus far not been successful.

Consequences of the long nuclear dance between Israel and the United States. Despite the US government’s silence on the issue, circumstantial evidence that Israel detonated a nuclear explosive device off the coast of South Africa on September 22, 1979, with the assistance of South Africa, keeps building. Such a test means that Israel and South Africa are in violation of the Limited Test Ban Treaty.

Israel’s nuclear program has vexed the diplomats of a number of presidential administrations over the years, beginning with that of John F. Kennedy, the last American president to attempt to stop Israel from obtaining nuclear weapons. The history of Israeli subterfuge and American indulgence that enabled Israel to sidestep what was ostensibly American nonproliferation policy in the 1960s and '70s has been well told. The current US policy of silence on Israel’s nuclear capabilities has its roots in an unwritten agreement made during Richard Nixon’s presidency, under which the United States would not pressure Israel to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), and Israel would keep quiet about testing or otherwise publicly declaring its nuclear weapons. This fed into the Israeli mantra that it “will not be the first country to introduce nuclear weapons into the Middle East.”

Over the decades since that formulation was first uttered, Israel’s public silence about its nuclear capabilities has taken on the status of a sacred obligation, backed up by stringent domestic law that guarantees harsh punishment for those who willfully transgress it. After revealing some of Israel’s nuclear secrets to the British press, Vanunu was captured by Israeli agents and spent 17 years in an Israeli prison, 13 of them in solitary confinement. He was released in 1993 and later re-arrested.

Israeli sensitivity about its nuclear program has been transferred, so that American officials show deference to Israel’s desire for silence. Not only has no American president answered questions in public regarding Israel’s nuclear capability; the US government regularly admonishes federal employees holding clearances not to discuss Israel’s nuclear status—and backs this admonishment with the threat of punishment. This reticence to publicly discuss the Israeli nuclear program has spread to our NATO partners as well, though not to as great an extent.

The rationale for US silence on Israeli violations was established when the NPT was negotiated and close to being opened for signature. Arab country signatures were obtained under an assumption: The United States would induce Israel to carry out a public statement made by its prime minister and sign the treaty. In fact, Israel did not sign and already possessed its first nuclear weapons—something that US officials knew. But they thought they had an Israeli commitment not to test nuclear weapons, so the Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT) violation in 1979 was also a violation of an understanding, in place for more than a decade, between Israel and the United States.

This duplicity had no effect; the United States government apparently deems the political problems stemming from an admission of Israel’s possession of nuclear weapons and test ban violations to override other considerations—including its oft-stated support for international rules of law established by nuclear arms control treaties. Concerns about Israeli nuclear weapons were not always so easily shoved aside.

The thought that Israeli nuclear weapons could be a catalyst for a proliferation breakout in the region induced the UN General Assembly, on December 11, 1979, to adopt a resolution entitled “Israeli Nuclear Armament” in which it said that “the development of nuclear capability by Israel would further aggravate the already dangerous situation in the region and further threaten international peace and security.” The General Assembly then requested the Secretary-General, with the assistance of qualified experts, to prepare a study on Israeli nuclear armament. Accordingly, the Secretary-General appointed an international group of five scholars, denoted the “Group of Experts,” who completed and submitted their results on June 19, 1981. The study concluded that “the possession of nuclear weapons by Israel would be a seriously destabilizing factor in the already tense situation prevailing in the Middle East, in addition to being a serious danger to the cause of non-proliferation in general.” The study added that adherence by Israel to a nuclear-weapon free zone in the Middle East with accession to the NPT would “avoid the danger of a nuclear arms race in the Middle East.”

The report was completed less than two weeks after Israel’s attack on an Iraqi nuclear reactor. Still to come was an Israeli attack on a fledgling secret reactor site in Syria in 2007 and the Iran situation, showing that proliferation in the region was proceeding apace. The United States took no action in response to the UN report, which was about the dangers of nuclear weapons in the hands of an ally in the Middle East.

The report did not envision how Middle East politics would change in the following years—mainly because of the rise of Iran’s influence and power, aided by the ill-conceived US war with Iraq. The Arab monarchies, particularly the Saudis, are now more afraid of Iran and its nuclear potential than they are of Israel’s nuclear weapons. The core arguments for stopping Iran’s nuclear program could be said to be encapsulated in the quoted statements from the report of the Group of Experts, with “Israel” replaced by “Iran.”

The US response to those statements as applied to Israel was a virtual yawn, even though Israel had already violated the Limited Test Ban Treaty. Applying those statements to Iran, however—especially when coupled to Israel’s perception of an existential Iranian nuclear threat—galvanized the United States into organizing for action. The result was the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—popularly referred to as “the Iran agreement”—a time-limited agreement significantly curtailing Iran’s nuclear program and its ability to quickly develop nuclear weapons. This agreement, which does not have the status of a treaty, will be backed up by the threat of the return of any sanctions on Iran that will have been removed via implementation of the agreement. The threat of military action also hovers in the background.

Why the United States should admit that Israel and South Africa violated the Limited Test Ban Treaty. The US dilemma is understandable. Israel’s half-century of refusing to publicly admit the existence of its nuclear arsenal would present difficulties for the bilateral relationship, if the United States were to unilaterally declare not only its knowledge of Israel’s weapons, but its knowledge of Israel’s violation of the Limited Test Ban Treaty.

But must the United States accept forever a position of silence—one that diminishes US credibility as a champion of international arms control agreements? It may be that admitting the existence of Israel’s nuclear arsenal would present some additional problems for regional peace and politics in the Middle East today, but would they be as dire as suggested by the Group of Experts in 1981? Thirty-six years have passed since the (A) 747 event, and there is widespread understanding—including among Israel’s adversaries in the Middle East—that Israel has amassed a significant nuclear arsenal (believed to range from 80-200 warheads). So it isn’t the case that an admission of the arsenal by Israel or the United States would be treated as a revelation of heretofore-unknown facts. Arab leaders understand that their security is enhanced by the NPT and would suffer were they to abandon the treaty. And the lesson of sanctions for Iran is now out there for potential proliferators to see. Thus, rhetoric aside, the admission by Israel or the United States of Israel’s nuclear weapons status is unlikely to cause a political tsunami in the United Nations, or sweep aside the NPT, or otherwise cause a move by a group of countries to leave that treaty.

Continuing to hide Israel’s testing violation is a direct counter to the US claim that it stands for the rule of law and implies that the United States cannot be counted on to defend treaties if they are violated by Israel. This failure fosters cynicism about the seriousness of the United States and its allies on the restraining of nuclear weapons. In the wake of the Iran agreement, it underscores concerns that the United States has double standards on arms control when Israel is involved.

Just as it is appropriate to demand that Iran be transparent about its nuclear history in relation to its NPT violations, it is appropriate to demand that Israel and South Africa be transparent regarding their activities surrounding the violation of the Limited Test Ban Treaty. An investigation by the United Nations (via the International Atomic Energy Agency) of the Vela event with the full cooperation of its members would be an appropriate step toward resolving this issue. Surely, a credible claim of a violation of the LTBT deserves no less, especially at a time when nuclear sensitivities in the Middle East and elsewhere have reached such a high level.

The question is: What should the international community do about Israel’s and South Africa’s violation? Perhaps some would argue that a violation of a nuclear arms control treaty occurring decades ago should be treated as if a statute of limitations applies. But that violation has undoubtedly aided the development of sophisticated nuclear weapons that can murder millions. There should be no statute of limitations for any violation of international law that has resulted or can result in a holocaust. The ultimate decision on sanctions for the violation should be left to the United Nations.

In any case, if the US government’s silence and cover-up of Israel’s violation of the Limited Test Ban Treaty continues, and the arms control and nonproliferation community acquiesces in it, what shall we make of all the grand-sounding rhetoric we have heard for more than four decades about the importance of international nuclear arms control treaties?