The New York Times: Decades Later, Sickness Among Airmen After a Hydrogen Bomb Accident

/June 19, 2016 By Dave Phillips, The New York Times

It was a late winter night in 1966 and a fully loaded B-52 bomber on a Cold War nuclear patrol had collided with a refueling jet high over the Spanish coast, freeing four hydrogen bombs that went tumbling toward a farming village called Palomares, a patchwork of small fields and tile-roofed white houses in an out-of-the-way corner of Spain’s rugged southern coast that had changed little since Roman times.

It was one of the biggest nuclear accidents in history, and the United States wanted it cleaned up quickly and quietly. But if the men getting onto buses were told anything about the Air Force’s plan for them to clean up spilled radioactive material, it was usually, “Don’t worry.”

“There was no talk about radiation or plutonium or anything else,” said Frank B. Thompson, a then 22-year-old trombone player who spent days searching contaminated fields without protective equipment or even a change of clothes. “They told us it was safe, and we were dumb enough, I guess, to believe them.”

Mr. Thompson, 72, now has cancer in his liver, a lung and a kidney. He pays $2,200 a month for treatment that would be free at a Veterans Affairs hospital if the Air Force recognized him as a victim of radiation. But for 50 years, the Air Force has maintained that there was no harmful radiation at the crash site. It says the danger of contamination was minimal and strict safety measures ensured that all of the 1,600 troops who cleaned it up were protected.

Interviews with dozens of men like Mr. Thompson and details from never before published declassified documents tell a different story. Radiation near the bombs was so high it sent the military’s monitoring equipment off the scales. Troops spent months shoveling toxic dust, wearing little more protection than cotton fatigues. And when tests taken during the cleanup suggested men had alarmingly high plutonium contamination, the Air Force threw out the results, calling them “clearly unrealistic.”

John H. Garman was in the United States Air Force when, in 1966, a fully loaded B-52 bomber on a Cold War nuclear patrol collided with a refueling jet high over the Spanish coast, freeing four hydrogen bombs that went tumbling toward a coastal farming village called Palomares. Mr. Garman was among those who were first on the scene of the crash. CreditRaymond McCrea Jones for The New York Times

In the decades since, the Air Force has purposefully kept radiation test results out of the men’s medical files and resisted calls to retest them, even when the calls came from one of the Air Force’s own studies.

Many men say they are suffering with the crippling effects of plutonium poisoning. Of 40 veterans who helped with the cleanup who The New York Times identified, 21 had cancer. Nine had died from it. It is impossible to connect individual cancers to a single exposure to radiation. And no formal mortality study has ever been done to determine whether there is an elevated incidence of disease. The only evidence the men have to rely on are anecdotes of friends they watched wither away.

“John Young, dead of cancer ... Dudley Easton, cancer ... Furmanksi, cancer,” said Larry L. Slone, 76, in an interview, laboring through tremors caused by a neurological disorder.

At the crash site, Mr. Slone, a military police officer at the time, said he was given a plastic bag and told to pick up radioactive fragments with his bare hands. “A couple times they checked me with a Geiger counter and it went clear off the scale,” he said. “But they never took my name, never followed up with me.”

Monitoring of the village in Spain has also been haphazard, declassified documents show. The United States promised to pay for a public health program to monitor the long-term effects of radiation there, but for decades provided little funding. Until the 1980s, Spanish scientists often relied on broken and outdated equipment, and lacked the resources to follow up on potential ramifications, including leukemia deaths in children. Today, several fenced-off areas are still contaminated, and the long-term health effect on villagers is poorly understood.

Many of the Americans who cleaned up after the bombs are trying to get full health care coverage and disability compensation from the Department of Veterans Affairs. But the department relies on Air Force records, and since the Air Force records say no one was harmed in Palomares, the agency rejects claims again and again.

The Air Force also denies any harm was done to 500 other veterans who cleaned up a nearly identical crash in Thule, Greenland, in 1968. Those veterans tried to sue the Defense Department in 1995, but the case was dismissed because federal law shields the military from negligence claims by troops. All of the named plaintiffs have since died of cancer.

In a statement, the Air Force Medical Service said it had recently used modern techniques to reassess the radiation risk to veterans who cleaned up the Palomares accident and “adverse acute health effects were neither expected nor observed, and long-term risks for increased incidence of cancer to the bone, liver and lungs were low.”

The toxic aftermath of war is often vexing to untangle. Damage is hard to quantify and all but impossible to connect to later problems. Recognizing this, Congress has passed laws in the past to give automatic benefits to veterans of a few specific exposures — Agent Orange in Vietnam or the atomic tests in Nevada, among others. But no such law exists for the men who cleaned up Palomares.

If the men could prove they were harmed by radiation, they would have all costs for their associated medical care covered and would get a modest disability pension. But proof from a secret mission to clean up an invisible poison decades ago has proved elusive. So each time the men apply, the Air Force says they were not harmed and the department hands out denials.

“First they denied I was even there, then they denied there was any radiation,” said Ronald R. Howell, 71, who recently had a brain tumor removed. “I submit a claim, and they deny. I submit appeal, and they deny. Now I’m all out of appeals.” He sighed, then continued. “Pretty soon, we’ll all be dead and they will have succeeded at covering this whole thing up.”

The debris of a crashed American plane in January 1966 in Palomares, Spain.CreditKit Talbot

The Day the Bombs Fell

A 23-year-old military police officer named John H. Garman arrived by helicopter at the crash site on Jan. 17, 1966, a few hours after the bombs blew.

“It was just chaos,” Mr. Garman, now 74, said in an interview at his home in Pahrump, Nev. “Wreckage was all over the village. A big part of the bomber had crashed down in the yard of the school.”

He was one of the first on the scene, and joined a half-dozen others to hunt for the four missing nuclear weapons. One bomb had thudded into a soft sandbank near the beach and crumpled but remained intact. Another had dropped into the ocean, where it was found unbroken two months later, after a frenzied hunt.

The other two hit hard and exploded, leaving house-size craters on either side of the village, according to a secret Atomic Energy Commission report that has since been declassified. Built-in safeguards prevented nuclear detonations, but explosives surrounding the radioactive cores blasted a fine dust of plutonium over a patchwork of houses and fields full of ripe, red tomatoes.

A throng of residents led Mr. Garman to the plutonium-covered craters, where they peered down at the shattered wreckage, not knowing what to do. “We didn’t have any radiation detectors yet, so we had no idea if we were in danger,” he said. “We just stood there looking down at the hole.”

Atomic Energy Commission scientists soon arrived and took Mr. Garman’s clothes because they were contaminated, he said, but told him he would be fine. Twelve years later, he got bladder cancer.

Plutonium does not emit the type of penetrating radiation often associated with nuclear blasts, which causes immediately obvious health effects, such as burns. It shoots off alpha particles that travel only a few inches and cannot penetrate the skin. Outside the body, scientists say, it is relatively harmless, but specks absorbed in the body, usually through inhaling dust, shoot off a continuous shower of radioactive particles thousands of times a minute, gradually exacting damage that can cause cancer and other diseases decades later. A microgram, or a millionth of a gram, in the body is considered potentially harmful. According to declassified Atomic Energy Commission reports, the bombs at Palomares released an estimated seven pounds — more than 3 billion micrograms.

Victor B. Skaar, now 79, worked with the testing team at the crash site. “Did we follow protocol?” he said. “Hell, no. We had neither the time nor the equipment.”CreditRaymond McCrea Jones for The New York Times

The day after the crash, busloads of troops started arriving from United States bases, bringing radiation-detection equipment. William Jackson, a young Air Force lieutenant, helped with some of the first testing near the craters, using a hand-held alpha particle counter that could measure up to two million alpha particles per minute.

“Almost everywhere we pointed the machine it pegged at the highest reading,” he said. “But we were told that type of radiation would not penetrate the skin. We were told it was safe.”

The Pentagon focused on finding the bomb lost in the ocean and largely ignored the danger of loose plutonium, the Air Force personnel at the site said. Troops traipsed needlessly through highly contaminated tomato fields with no safety gear. Many came to gawk at the shattered bombs in the first few days. “Once I went to check on the G. I.s and found them dangling their legs into the crater,” Mr. Jackson said. “Just sitting there, eating their box lunches.”

Accounts of the crash became front-page news in Europe and the United States. American and Spanish officials immediately tried to cover up the accident and play down the risk. They blocked off the village and denied nuclear weapons or radiation were involved in the crash. When an American reporter spotted men wearing white coveralls, a military press officer told him, “Oh, they’re members of the postal detachment.”

Once existence of the bombs leaked, more than a month later, the United States admitted that one bomb, not two, had “cracked,” but had released only a “small amount of basically harmless radiation.”

Today the two exploded warheads would be known as dirty bombs, and would probably cause evacuations. At the time, in order to minimize the significance of the blast, the Air Force let villagers remain in place.

Officials invited the news media to witness Spain’s minister of information, Manuel Fraga Iribarne, and United States ambassador, Angier Biddle Duke, splashing on a nearby beach to show the area was safe. Mr. Duke told reporters, “If this is radioactivity, I love it.”

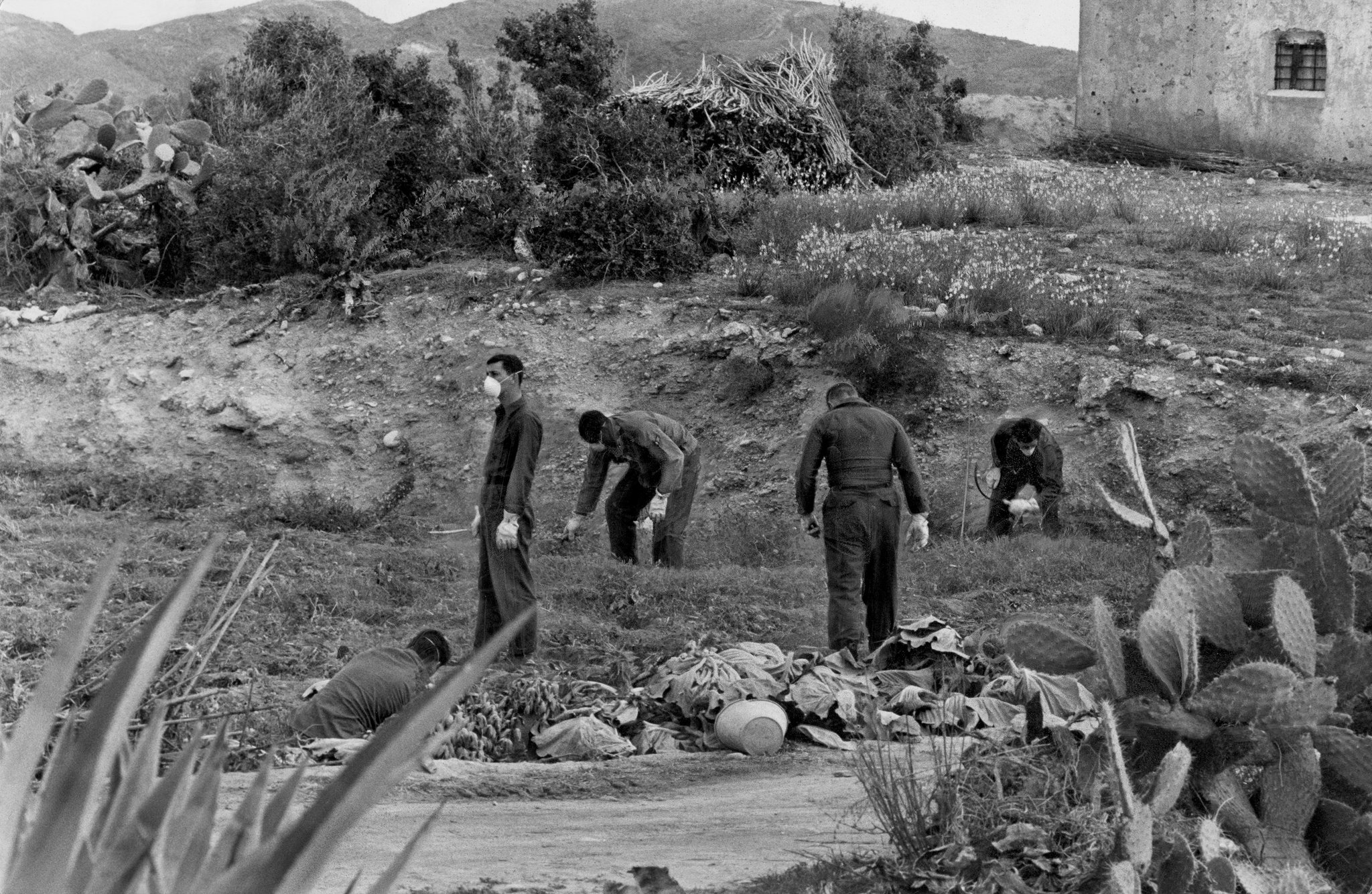

Air Force personnel wearing masks and gloves working in the fields where three of the bombs were found.CreditU.S. Air Force

A Hurried Cleanup

Fearing that the bombs could damage the tourism industry, Spain insisted the mess be cleaned up before summer.

Within days, troops were hacking down contaminated fields of tomato vines with machetes. Though scientists overseeing the cleanup knew plutonium dust posed the greatest danger, military commanders had the troops throw thousands of truckloads of vines into chipping machines, then burned much of the debris near the village.

Some men doing the dustiest work were given coveralls and paper surgical masks for safety, but a later report by the Defense Nuclear Agency said, “It is doubtful that the use of the surgical mask served more than a psychological barrier.”

“If it did something for your psychology to wear one, you were privileged to wear one,” the chief scientific adviser, Dr. Wright H. Langham, told Atomic Energy colleagues in a secret briefing afterward. “It wouldn’t do you any good in the way of protection, but if you felt better, we let you wear it.”

Commenting on safety at the cleanup, Dr. Langham, who is perhaps best known now for his role in secret experiments in which hospital patients in the United States were unwittingly injected with plutonium, told colleagues, “Most of the time it would hardly meet the standards of the health physics manuals.”

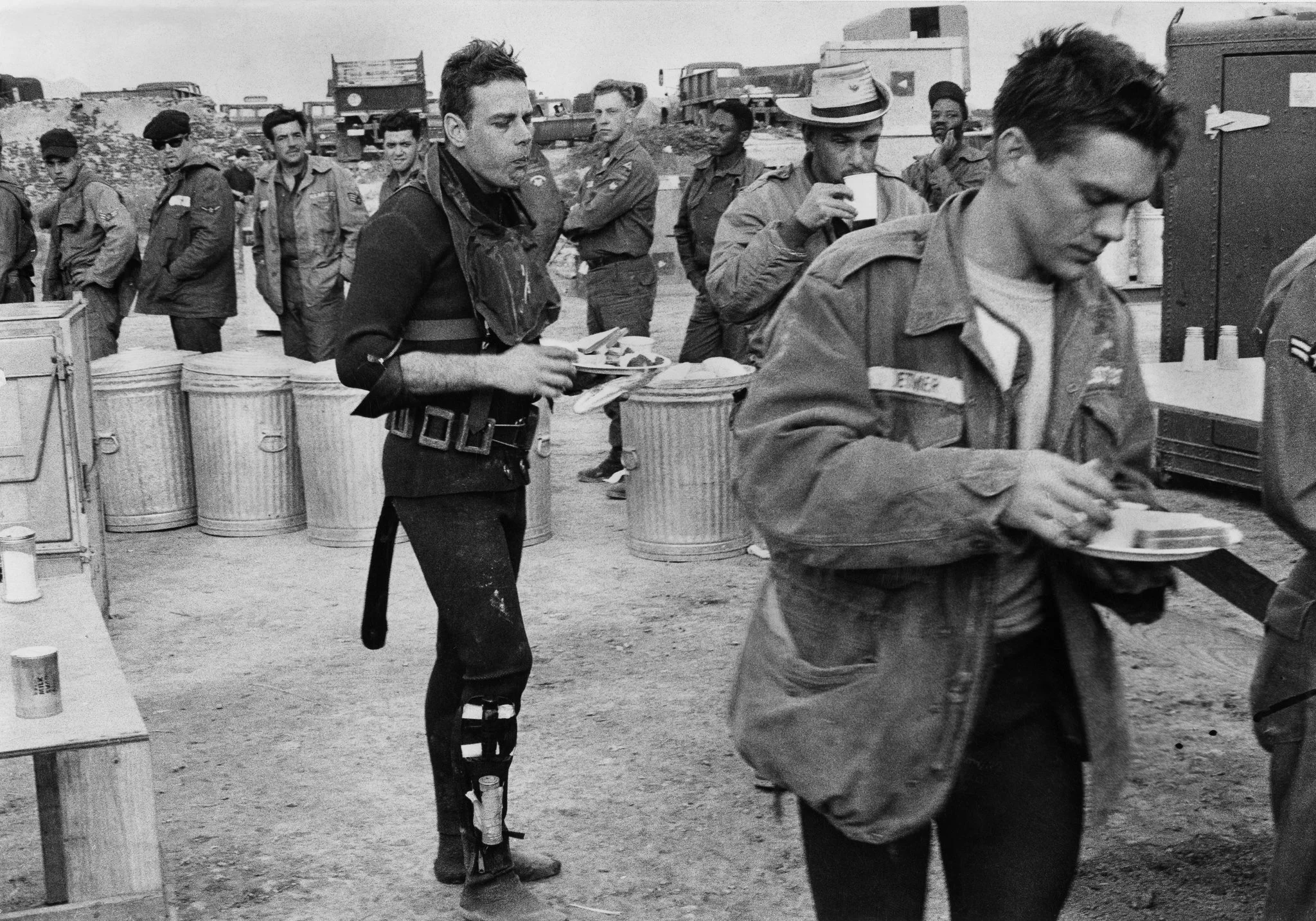

The Air Force bought tons of contaminated tomatoes from local fields that the Spanish public refused to eat. To assure the public there was no danger, commanders fed the tomatoes to the troops. Though the risk from eating plutonium is much lower than the risk from inhaling it, it is still not safe.

Mr. Garman’s 1979 military clinical records, which indicate plutonium exposure in Spain.CreditRaymond McCrea Jones for The New York Times

“Breakfast, lunch and dinner. We had them until we were sick of them,” said Wayne Hugart, 74, who was a military police officer at the site. “They kept saying there was nothing wrong with them.”

In all, the Air Force cut down 600 acres of crops and plowed under the contaminated dirt. Troops scooped up 5,300 barrels of soil from the most radioactive areas near the craters and loaded the barrels on ships to be buried in a secure nuclear waste storage site in South Carolina.

Spanish and American authorities assured villagers that they had nothing to fear. The villagers, accustomed to living in a dictatorship, did little to protest. “Even if some people here might have wanted to know more, Franco was in charge, so everybody was too scared to ask anything,” said Antonio Latorre, a villager who is now 78.

To assure villagers their homes were safe, the Air Force sent young airmen into local houses with hand-held radiation detectors. Peter M. Ricard, then a 20-year-old cook with no training on the equipment, remembers being told to perform scans of anything locals wanted, but to keep his detector turned off.

“We were just supposed to feign our readings so we didn’t cause turmoil with the natives,” he said in an interview. “I often think about that now. I wasn’t too smart back then. They say do it and you just say, ‘Yes, sir.’”

United States Air Force personnel working on cleanup and recovery were often fed local produce from Palomares. CreditKit Talbot

Tests Thrown Out

During the cleanup, a medical team gathered more than 1,500 urine samples from the cleanup crew to calculate how much plutonium they were absorbing. The higher the level in the samples, the greater the health hazard.

The records of those tests remain perhaps the most prominent artifact from the cleanup. They show about only 10 of the men absorbed more than the allowed safe dose, and the rest of the 1,500 responders were not harmed. The Air Force today relies on the results to argue that the men were never harmed by radiation. But the men who actually did the testing say the results are deeply flawed and are of little use in determining who was exposed.

“Did we follow protocol? Hell, no. We had neither the time nor the equipment,” said Victor B. Skaar, now 79, who worked on the testing team. The formula for determining the contamination level required collecting urine for 12 hours, but he said he was able to get only a single sample from many men. And others, he said, were never tested at all.

He sent samples to the Air Force’s chief of radiation testing, Dr. Lawrence T. Odland, who started seeing alarmingly high results. Dr. Odland decided the extreme levels did not indicate a true health threat, but were caused by plutonium loose in the camp that contaminated the men’s hands, their clothes and everything else. He threw out about 1,000 samples — 67 percent of the results — including all samples from the first days after the blasts when exposure was probably highest.

Now 94 and living in a rambling Victorian house in Hillsboro, Ohio, where a photo from the Greenland crash hangs in his hall, Dr. Odland questioned his decision.

“We had no way of knowing what was from contamination and what was from inhalation,” he said. “Was the world ending or was everything fine? I just had to make a call.”

He said he never got accurate results for hundreds of men who may have been contaminated. In addition, he soon realized plutonium lodged in the lungs could not always be detected in veterans’ urine, and men with clean samples might still be contaminated.

“It’s sad, sure, it’s sad,” he said. “But what can you do? You can’t take the plutonium out; you can’t cure the cancer. All you can do is bow your head and say you are sorry.”

Dr. Lawrence T. Odland, the Air Force’s chief of radiation testing, persuaded the Air Force in 1966 to set up a permanent “Plutonium Deposition Registry Board” to monitor the men for life, but the program was terminated.CreditRaymond McCrea Jones for The New York Times

Monitoring Program Killed

Convinced that the urine samples were inadequate, Dr. Odland persuaded the Air Force in 1966 to set up a permanent “Plutonium Deposition Registry Board” to monitor the men for life.

Experts from the Air Force, Army, Navy, Veterans Administration (now the Department of Veterans Affairs) and Atomic Energy Commission met to establish the program shortly after the cleanup. In welcoming remarks, the Air Force general in charge said the program was “essential” and following the men to their graves would provide “urgently needed data.”

The organizers proposed not notifying troops of their radiation exposure and keeping details of testing out of medical records, according to minutes of the meeting, out of concern notifying them could “set a stage for legal action.”

The plan was to have Dr. Odland’s staff follow the men. Within months, though, he had hit a wall.

“He is not able to get the support from the Department of Defense to go after the remaining people or set up a real registry because of the sleeping-dog policy,” an Atomic Energy Commission memo from 1967 noted.

“The sleeping dog policy? It was to leave it alone. Let it lie. I didn’t agree. Hell no, I didn’t agree,” Dr. Odland said. “Everyone decided we should watch these guys, take care of them. And then from somewhere up high they decided it was better to get rid of it.”

Dr. Odland did not know who gave the order to terminate the program, but said since the board included all the military branches and the veterans agency, it likely came from top-level officials.

The Air Force officially dismantled the program in 1968. The “permanent” board had met just once.

Arthur Kindler, at right in center photo, was among those Air Force personnel responding to the crash.CreditRaymond McCrea Jones for The New York Times

After Cleanup, Sickness

Troops started to get sick soon after the cleanup ended. Healthy men in their 20s were crippled by joint pain, headaches and weakness. Doctors said it was arthritis. A young military policeman was plagued by sinus swelling so acute that he would bang his head on the floor to distract himself from the pain. Doctors said it was allergies.

Several men got rashes or growths. An airman named Noris N. Paul had cysts severe enough that he spent six months in the hospital in 1967 getting skin grafts. He also became infertile.

“No one knew what was wrong with me,” Mr. Paul said.

A grocery supply clerk named Arthur Kindler, who had been so covered in plutonium while searching the tomato fields a few days after the blast that the Air Force made him wash off in the ocean and took his clothes, got testicular cancer and a rare lung infection that nearly killed him four years after the crash. In the years since, he has had cancer of his lymph nodes three times.

“It took me a long time to start to realize this maybe had to do with cleaning up the bombs,” Mr. Kindler, 74, said in an interview from his home in Tucson. “You have to understand, they told us everything was safe. We were young. We trusted them. Why would they lie?”

Mr. Kindler filed twice for help from the Department of Veterans Affairs. “They always denied me,” he said. “Eventually, I just gave up.”

Mr. Kindler, who had been so covered in plutonium while searching the tomato fields a few days after the crash that the Air Force made him wash off in the ocean and took his clothes, got testicular cancer and a rare lung infection that nearly killed him four years after the crash.CreditRaymond McCrea Jones for The New York Times

Spain’s Monitoring

The United States promised to pay for long-term monitoring of health in the village, but for decades it provided only about 15 percent of funding, with Spain paying the rest, according to a declassified Department of Energy summary. Broken air-monitoring stations went unfixed and equipment was often old and unreliable. In the early 1970s, an Atomic Energy Commission scientist noted, the Spanish field monitoring team consisted of a lone graduate student.

Reports of two children dying of leukemia during that time went uninvestigated. The lead Spanish scientist monitoring the population told American counterparts in a 1976 memo that, in light of the leukemia cases, Palomares needed “some kind of medical surveillance of the population to keep watch for diseases or deaths.” None was created.

In the late 1990s, after years of pressure from Spain, the United States agreed to increase funding. New surveys of the village found extensive contamination that had gone undetected, including some areas where radiation was 20 times the permissible level for inhabited areas. In 2004, Spain quietly fenced off the most contaminated land near the bomb craters.

Since then, Spain has urged the United States to finish cleaning the site.

Because of the uneven monitoring, the effect on public health is far from clear. A small mortality study in 2005 found cancer rates had gone up in the village compared with similar villages in the region, but the author, Pedro Antonio Martínez Pinilla, an epidemiologist, cautioned that the results could be because of random error, and urged more study.

At that time, a United States Department of Energy scientist, Terry Hamilton, proposed another study, noting problems in Spain’s monitoring techniques. “It was clear the uptake of plutonium was poorly understood,” he said in an interview. The department did not approve his proposal.

Spanish officials say the fears may be overblown. Yolanda Benito, who heads the environmental department of Ciemat, Spain’s nuclear agency, said that medical checks showed no uptick in cancer in Palomares. “From a scientific point of view, there is nothing that allows us to draw a relationship between the cases of cancer in the local population and the accident,” she said.

About a fifth of the plutonium spread in 1966 is estimated to still contaminate the area. After years of pressure, the United States agreed in 2015 to clean up the remaining plutonium, but there is no approved plan or timetable.

Nolan F. Watson, also among those at the crash site, had problems with painful joints, kidney stones and localized skin cancer. In 2002, he was diagnosed with kidney cancer. In 2010, more cancer showed up in his remaining kidney. Recent abnormal blood tests suggested leukemia .CreditRaymond McCrea Jones for The New York Times

‘I’m Going to Speak My Piece’

On a recent rainy morning, Nona A. Watson, a retired science teacher in Buckhead, Ga., held open the door of a veterans medical center in Atlanta for her husband, Nolan F. Watson, who hobbled in, his shuddering hand unable to steady his cane.

As a 22-year-old dog handler, Mr. Watson slept in the dirt just feet from one of the bomb craters the day after the blast. A year later, he was racked by blinding headaches and hips so stiff he could barely walk. At the time, he asked the Department of Veterans Affairs for help. He said he was turned away. For years he had problems with painful joints, kidney stones and localized skin cancer. In 2002, he was diagnosed with kidney cancer, and one of his kidneys was removed. In 2010, more cancer showed up in his remaining kidney. Recent abnormal blood tests suggested leukemia.

“I think it ruined my life,” he said. “I was young, in good shape. But since that day, I’ve had problems all the time.”

Mr. Watson, now 73, had filed a claim with the veterans agency that was denied and he was in the process of appealing. Other veterans of Palomares had warned him that it was a waste of time. Only one Palomares veteran they knew of had succeeded in claiming harm from radiation, and it took 10 years, at which point he was bedridden with stomach cancer. But Mr. Watson wanted to come to the medical center to give personal testimony about his plutonium exposure.

In the center’s waiting room, his nose began to bleed.

A few years ago, after his first claim was denied, Mr. Watson’s wife began hunting down old government documents, hoping she might find something to prove the Air Force was covering up Palomares. Maybe, she thought, she could discover evidence that would make the authorities reconsider.

She turned up reports going back 40 years that confirmed the men’s stories of high radiation levels and poor safety standards. But her most striking find was an Air Force study from 2001 that reassessed the contamination in Palomares veterans. The study determined that the old urine tests were so flawed that they were “not useful” and the Air Force should retest the men.

Mrs. Watson knew no retesting had been done, so she called the Air Force Medical Service to ask why. When she could not get a clear answer, she asked her congressman at the time, Paul Broun, Republican of Georgia, to send a letter to the Air Force. When the congressman could not get a clear answer, either, he proposed legislation, which the House passed in 2013, requiring the Air Force to answer to Congress.

In 2013, the Air Force provided its legally required response in a letterto the House Armed Services Committee. To Mrs. Watson’s dismay, it echoed what she and the congressman had already been told: New testing recommended in the 2001 report “was not necessary” because troops had worn protective equipment, and the original urine tests showed that almost no one had been exposed to radiation. Declassified documents and witness accounts raise serious questions about the accuracy of the Air Force’s report to Congress.

After issuing the letter, the Air Force Medical Service quietly took down from its website the only public copy of the 2001 report.

As a 22-year-old dog handler, Mr. Watson slept in the dirt just feet from one of the bomb craters the day after the blast. CreditRaymond McCrea Jones for The New York Times

“I had gone into this thinking it was just an old mistake, but then I found they were still trying to cover it up,” Mrs. Watson said in an interview at her home.

Col. Kirk Phillips, who oversees the radiation health program for the Air Force Medical Service, said in a recent interview that the Air Force has tried its best to do right by the Palomares veterans. It took down the report because it did not want to raise the hopes of veterans and feared readers would find it “confusing.”

“We have a large number of veterans we believe were not exposed,” he said.

Radiation levels at Palomares were low, he said, and men wore safety equipment. Retesting them with more precise modern techniques, as the 2001 report suggested, could reveal even lower contamination levels, making it even less likely that the veterans would get compensation from the department.

“We think retesting could be a real mistake,” he said. “It could harm our veterans because we think it would find even lower levels of radiation.”

In the interest of giving Palomares veterans what he called “the benefit of the doubt,” he said, the Air Force stopped relying in 2013 on the old urine test results and instead assigned all troops who cleaned up the site a “worst-case scenario” dose based on ambient air readings of radiation from the time.

It gave them a dose of 0.31 rem — a very small dose too low to qualify veterans for department benefits. The Greenland veterans who cleaned up a similar crash have been assigned a dose of zero.

Mrs. Watson, who has studied Palomares’s test results and reports in detail, said the ambient air tests probably do not reflect what individuals working near the craters absorbed. “As far as I can tell, it’s not based on anything and won’t do anyone any good,” she said. “You wonder why they even bothered.”

As she waited at the medical center with her husband, she explained how they expected their appeal to fail. They had no proof. No matter what he said in his testimony, the department would refer to old urine samples to determine who was harmed. And Mr. Watson had never given a urine sample. He could not offer a new urine sample because cancer had taken most of his kidneys.

If successful with the appeal, Mr. Watson would have all of his medical costs covered and get modest monthly disability payments.

“But that’s not why I’m doing it,” he said as he dabbed at his nose. “I’m not about the money.”

He doubted he would live long enough to collect much. More than anything, he wanted the record straight. He wanted to tell the Air Force that he and the men he served with mattered enough to be told the truth.

“I’m going to speak my piece, dang it.” Mr. Watson said. “They know this whole thing is a lie.”

Raphael Minder contributed reporting.